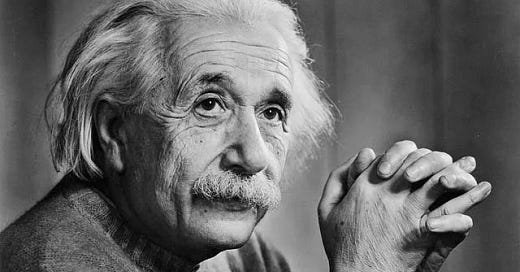

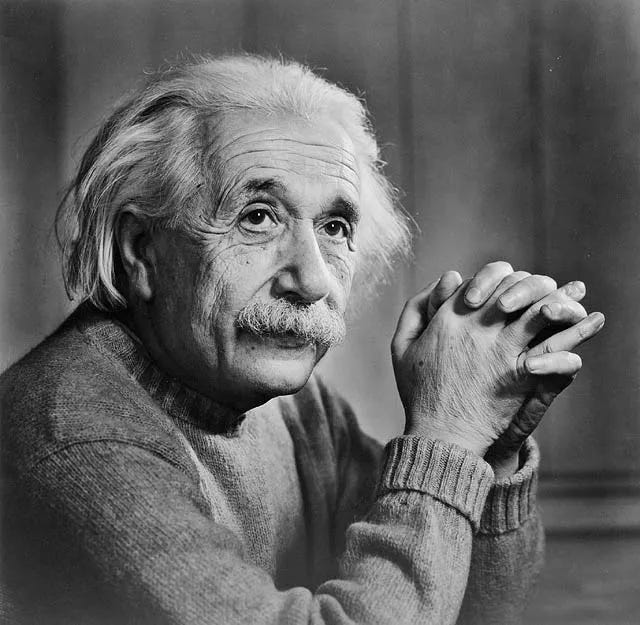

It is 70 years, almost to the day, since the death of surely the world’s most recognised scientist, Albert Einstein, and science is once again under threat.

Carl Sagan’s foreboding has, sadly, come true.

Despite all of science’s extraordinary advances, we are once again at the mercy of misinformation and good old-fashioned superstition, as horoscopes make their way into news bulletins and our critical faculties are subdued into submission by AI and the low-dose heroin drip of TikTok and Netflix.

But what is science, exactly? And why am I such a fanboy? Yes, science is facts and figures, numbers and data, hypotheses and experiments (no wonder it struggles to get media attention - I can see you stifling that yawn from here).

But at its root, science is simply questioning. No different to a child asking yet again, But why? This questioning is borne of pure curiosity - a desire to know the answer, to seek “the truth”. Closely related is wonder, which to me denotes curiosity combined with a sense of awe and delight. These are all attributes of the true scientist.

But the other essential element in this formula for science is the knowledge that we do not know. That we, as humans limited by our faculties, despite all our add-on technology, can never know the whole truth, just as a map can never completely represent its territory, otherwise it would be that territory. We can move further and further towards it, but like a curve to its asymptote, never quite reach it.

This knowing that, despite all our best efforts, we will always be partly wrong, requires humility. It is arguably the most important principle of science - and a fitting metaphor for our human place in the universe.

It is also where the foundation of science intersects with that of philosophy, in Socrates’ “All that I know is that I know nothing,” reminding us that wisdom begins by acknowledging our ignorance. Rory Stewart’s fascinating podcast on ignorance explores this in modern detail, even going so far as to suggest we might “celebrate” our ignorance. I see what he’s doing here, but the danger is that this is too easily misinterpreted, and that we instead fall further into Sagan’s dark prophecy. We must indeed acknowledge our ignorance, but still strive away from it.

Then there’s a second source of humility to factor into this scientific equation. All of our current knowledge, despite all its shortcomings, is built on countless hours of thought and mental toil of all the scientists that have gone before us. Not just the published geniuses like Marie Curie that we’ve all heard of, but all the unsung heroes whose less newsworthy contributions and negative-result experiments have gotten us to where science is today. And on whose coattails we ride.

The science I love, then, is this combination of curiosity and humility (squared). It is the opposite of unthinking acceptance. It is also the opposite of a blind faith that all that purports to be science should be automatically trusted. Like any human endeavour, science is of course subject to corruption, too. As soon as large amounts of money and power get involved (yes, those old chestnuts), scientists, and therefore science, are susceptible to all the usual vices, such as analytical bias at best, and plagiarism and falsified data at worst.

But this again is the beauty of true science. It will keep questioning, even when something is “proven”. The perpetual questioning is its own self-correcting device. It’s built into the system. No so-called authority can ever be afforded total acceptance.

Does this mean there is no such thing as experts in the sciences? Of course not. Experts, by definition, will know far more about their field than lay people. But the key is that we so-called experts (my area is prostate cancer) adhere to the that humble principle of science that we can never be certain. We might know more than most, but we’re a long way from knowing everything.

Einstein first published his theory of special relativity in 1905. But physicists are still not sure what reality even consists of! Are we waves or particles? Or wavicles?? We have to remember that progress can’t happen if we just accept what is thought to be “true” now.

Which introduces that other fundamental but hidden aspect of true science that most think of as belonging instead in the world of art: imagination.

Imagination is what takes us from Why? to What if? It is the exact opposite of unthinking acceptance and blind faith. It permits the human brain to soar to its highest stratosphere, absorbing countless data points, combining them and reconfiguring them in unknown ways through a mass of wet electrical circuitry and producing, somehow, from this biological goo of intelligence - a new idea!

Einstein was a big fan of imagination, as evidenced by his numerous quotes on it. My favourite: “I am enough of an artist to draw freely on my imagination. Imagination is more important than knowledge. Knowledge is limited. Imagination encircles the world.”

For science and its institutions to hold, we must chant not only Einstein’s e=mc^2, but science’s own formula like a mantra to ourselves and the world:

Science = curiosity x humility^2 (+ imagination)